When my Uncle Tom died, some years ago, I rang my cousin to offer sympathy and love, to share a few memories and to see if she and her sisters needed any help with the practical details. Coming from a family with an infamously sweet tooth, and knowing my cousin’s particular weakness for cake, I teased: “I’m a dab-hand at funeral cake, you know!” Her response was immediate and positive, and I found myself unexpectedly responsible for some memorial baking.

Like my uncle and cousin, I grew up with the idea that providing for someone is an everyday opportunity to show love. My Grandma loved baking, and we never went short of cake, pies, puddings or scones. She passed that love to her daughters and grandchildren. When my cousin came among us with a tray and asked, “Would you like some of the funeral cake that Paul’s made?” nobody batted an eyelid. It was the perfect expression of a family culture of providing and sharing, of finding joy in sweetness, even when the times are sad ones.

As a food writer, I have come across recipes and anecdotes about funeral cakes in several sources. Although I was surprised at first, the idea of a cake that marks the passing of someone loved and respected has come to make more and more sense to me. We mark so many important moments with food. After the excesses of Victorian mourning and the traumatic losses of the world wars, it was perhaps natural that we tried as a culture to minimise all expressions of grief and loss and to avoid reflecting on the reality of death at all. Recipes for funeral foods were lost, as we did away with anything that seemed to normalise contact with death. I have perceived a change, though, in the last thirty years or so. Alienated from traditional forms of mourning, people are looking again at how to mark the importance of lives lived well and love that remains.

For many Christian families, especially Catholics, it is common to celebrate funerals with the Eucharist. Buried within the layers of meaning and theology, the Eucharist is at heart a ritualised meal. The community gathers around a table to share bread and wine. Many other religious communities will be used to sharing food at home or around funeral services. In Wales and the English midlands, it was once common to employ the services of “sin-eaters,” who were given food over the body of the person who has died and were believed to consume their wrongdoing with that food, thus ensuring an effective transition to the afterlife. The origin of the practice is not well understood, although it only died out in the later years of the nineteenth century. It is believed to be the forerunner of Victorian and more modern funeral cakes.

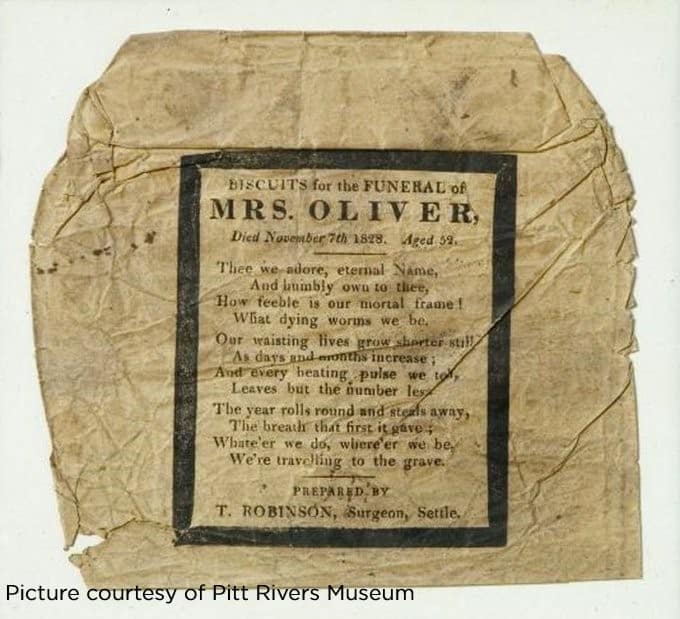

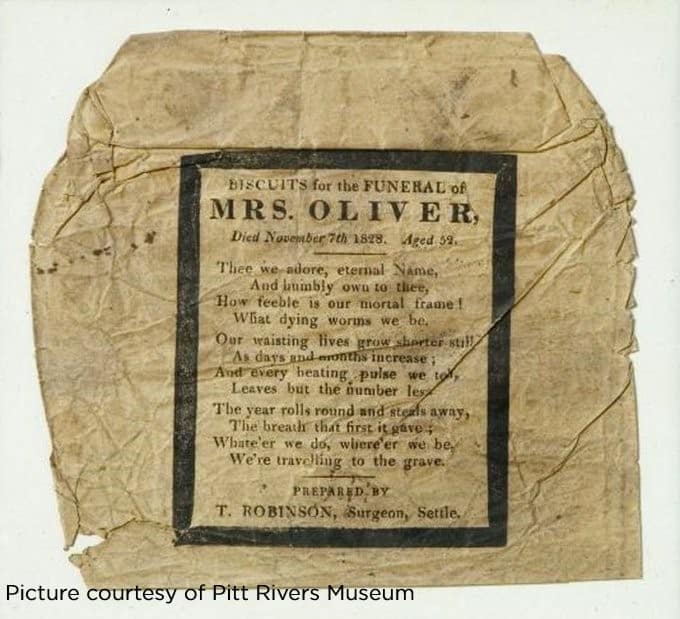

The recipes I’ve come across in my research fall broadly into three categories, according to their function: to announce a death, to thank guests for coming, and to show care for the bereaved. The first of these were usually simple shortcakes. Bakers and confectioners across northern England baked batches of such cakes, often impressed with designs such as crosses or hearts. Each was individually wrapped in paper printed with biblical verses or reassuring poetry and sealed with wax. Often, they would be delivered door to door by the baker’s boy, who informed the recipient of the passing and the funeral arrangements. I have seen examples of wrappers from many northern mill- and mining towns, so we can reasonably conclude these biscuits were relatively inexpensive.

At the other end of the scale is the recipe for funeral cakes to be found in Julie Duff’s wonderful book, Cakes Regional & Traditional. These are delicate sponge fingers, flavoured with fresh lemon peel and dried fruit. That they were, according to Duff, “served with sherry or wine” indicates they were enjoyed at wealthier homes than the biscuits just mentioned. These were offered as refreshment to those who had come to the funeral – a touch of luxury to thank people for coming.

Readers with Irish connections will be familiar with waking, and the importance it has in Irish culture. As soon as it is known that a member of the community has passed on, friends, neighbours and family will start to arrive at the family home to comfort the bereaved, pay their respects and keep vigil around the body. Most will bring a plate of sandwiches, a cake or some scones: nobody would expect the bereaved to cater for such numbers immediately after a death. The third sort of funeral cake I’ve come across comes from this desire to look after the newly-bereaved. Often, they are loaf cakes, easily sliced up for many visitors. Tea loaves predominate, as they are quick to make, requiring no time to “mature,” and are made from the kind of staple ingredients most home bakers have readily at hand. Given that the funeral will usually take place within a couple of days of the death, tea loaves make economic sense. They keep better than sponge cakes, so any left after the wake will do for the funeral tea, too.

To return, then, to my uncle’s funeral and the absolute right-ness of making a cake to mark his passing. What made it so right was our family’s experience of taking pleasure in sweet foods. I wonder what foods make sense to you and your experience of loss. To make a cake for family on these occasions is both a service and an honour, and I find the process deeply involving. Although it is a simple and familiar thing to be doing, it takes on particular significance. The actions, the smells the recipes, can all be evocative of the life of the person we’ve lost. Food, be it a cake or something else that it appropriate, is a gift of ourself: we have put time and care into it, and we are providing both real and symbolic nourishment to those we care for. We are doing for our bereaved family and friends what the person who has died is no longer able to do.

When you are planning how to mark the passing of those who have been significant in your own life, you might want to consider what part food should play. Who has fed you, and how? What foods speak to you of the love you’ve known, the joyful memories and stand-out moments? What foods might express your love and care for those who are hurting? I hope my reflections might provide a helpful starting-point for your own journey.

Paul Fogarty lives in the north of England, where he loves to have people gather around his table, to share good times and good food. He learnt to cook in school: he learnt to eat in France. He has hosted a private dining club for the last 28 years and we would encourage you to read his wonderful blog

To receive our newsletters and information about new blogs – please sign up here.